In a landmark decision reshaping administrative and environmental law, the Supreme Court’s ruling in *West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency* marked a pivotal moment in the debate over federal agency authority. At its core, the case questioned whether the EPA could regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants by mandating a systemic shift toward renewable energy under the Clean Air Act—a question the Court answered with a resounding “no.”

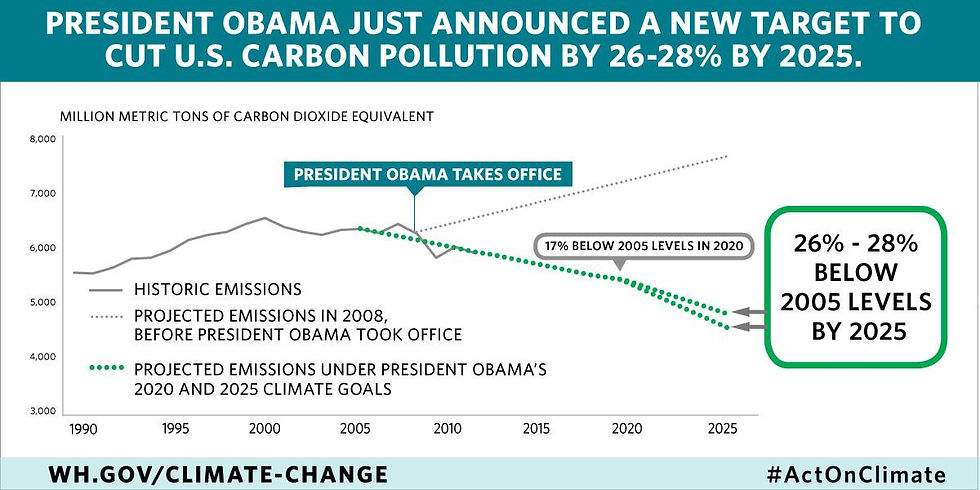

The dispute traces back to the Obama-era Clean Power Plan (CPP), which sought to reduce carbon emissions by requiring states to transition from coal and natural gas to wind, solar, and other cleaner energy sources.

The EPA justified this “generation shifting” approach under Section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act, framing it as the “best system of emission reduction.” But the plan faced immediate legal challenges from coal-reliant states and industry groups, who argued it overstepped the EPA’s statutory authority.

The Supreme Court stayed the CPP in 2016, and the Trump Administration later replaced it with the narrower Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) Rule, which focused on plant-level efficiency upgrades. When the D.C. Circuit struck down the ACE Rule in 2021 for being “arbitrary and capricious,” the stage was set for the Supreme Court to resolve whether the EPA’s original vision for the CPP was ever legally permissible.

Central to the case was whether Section 111(d) granted the EPA power to impose industry-wide caps through generation shifting—a method the agency argued was necessary to address climate change but critics likened to setting national energy policy.

The Court’s 6-3 majority, led by Chief Justice Roberts, rejected the EPA’s interpretation, invoking the “major questions doctrine.”

This principle requires Congress to explicitly authorize agencies to decide issues of profound economic or political significance. Here, the Court found no such clear mandate in the Clean Air Act for the EPA to effectively restructure the energy sector.

While the statute allows the EPA to regulate emissions through “systems” applied at individual plants, the majority concluded that mandating a nationwide shift from coal to renewables crossed into policymaking territory reserved for Congress.

The decision’s ramifications extend far beyond environmental regulation. For the EPA, the ruling signals that ambitious climate policies—particularly those with transformative economic impacts—will need unambiguous congressional approval. This creates immediate hurdles for federal efforts to combat climate change, effectively shifting the burden to a gridlocked legislature to define the scope of agency action.

Meanwhile, the energy sector faces a regulatory landscape where fossil fuel plants are insulated from federal mandates to reduce output or adopt renewables, potentially slowing the transition to cleaner energy absent state or congressional action.

Administratively, The Case reinforces a judicial trend constraining executive agency power. By elevating the major questions doctrine, the Court has underscored that agencies cannot rely on vague or ancillary statutory language to justify expansive rules with sweeping societal consequences.

This precedent echoes recent skepticism of administrative authority in cases like *NFIB v. OSHA* (2022), where the Court blocked a federal vaccine mandate, and signals a judiciary increasingly wary of what it views as executive overreach.

Ultimately, the decision underscores a foundational tension in modern governance: How aggressively can federal agencies address pressing issues like climate change without explicit directives from Congress? While the ruling leaves room for narrower, plant-specific EPA regulations, it stifles bold, systemic approaches absent legislative buy-in.

The Court’s decision sends a clear message: federal agencies cannot bypass Congress when making decisions of vast economic and political significance. By invoking the "major questions doctrine," the Court reaffirmed that only Congress—not unelected agency officials—has the authority to approve transformative policies.

This ruling underscores the importance of democratic accountability in governance, ensuring that major regulatory actions reflect the will of the people as expressed through their elected representatives. Moving forward, agencies must seek explicit congressional approval for sweeping changes, reinforcing the foundational principle that in a democracy, power flows from the people to their legislature—not the other way around.

Comments