The creation of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) by executive action in 2025—without explicit congressional authorization—has sparked significant legal debate. In the wake of two landmark Supreme Court decisions, West Virginia v. EPA (2022) and Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (2024), the legality of DOGE hinges on whether its establishment and operations align with the new judicial constraints on federal agency power.

These rulings have fundamentally reshaped administrative law, emphasizing that transformative policies require clear congressional approval and that courts, not agencies, hold the final say on statutory interpretation.

Also Read,

" Major Questions" and the End of "Chevron"

The Supreme Court’s 2022 decision in West Virginia v. EPA 597 U.S. 697 (2022), introduced a stricter application of the major questions doctrine, which holds that agencies cannot address issues of “vast economic or political significance” without explicit congressional authorization.

The Court struck down the EPA’s Clean Power Plan, ruling that the agency overstepped its authority by attempting to restructure the energy sector without clear statutory backing. This decision signaled a shift toward judicial skepticism of agency overreach, particularly in areas with broad societal impact.

Two years later, in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo 603 U.S. 369 (2024), the Court went a step further by overturning the Chevron deference doctrine, which had allowed courts to defer to agencies’ reasonable interpretations of ambiguous statutes.

The Court held that judges must independently assess whether an agency’s actions align with congressional intent, rather than deferring to agency expertise.

This ruling effectively curtailed agencies’ ability to expand their authority through creative statutory interpretations.

Together, these decisions create a high bar for agencies like DOGE to justify their existence and actions.

The establishment of DOGE by executive order, without specific legislative approval, raises several red flags under the major questions doctrine and the post-Loper Bright framework:

Lack of Clear Congressional Authorization: DOGE’s creation via executive action, rather than through legislation, directly implicates the major questions doctrine. If DOGE’s mandate involves significant reforms—such as sweeping budget cuts, agency reorganizations, or privatization of federal services—courts will demand clear textual evidence that Congress authorized such authority. Broad or vague statutes, like the President’s general reorganization authority, are unlikely to suffice for transformative actions.

Judicial Scrutiny Under Loper Bright: With the end of Chevron deference, courts will no longer accept DOGE’s self-proclaimed authority under ambiguous statutory language. For example, if DOGE cites a law like the Paperwork Reduction Act to justify its efficiency reforms, judges will independently analyze whether Congress intended that statute to empower a new department with expansive regulatory reach. Without explicit legislative backing, DOGE’s actions are vulnerable to invalidation.

Economic and Political Significance:If DOGE’s initiatives impact federal operations, employment, or industry standards, courts will treat these as “major questions” requiring congressional buy-in.

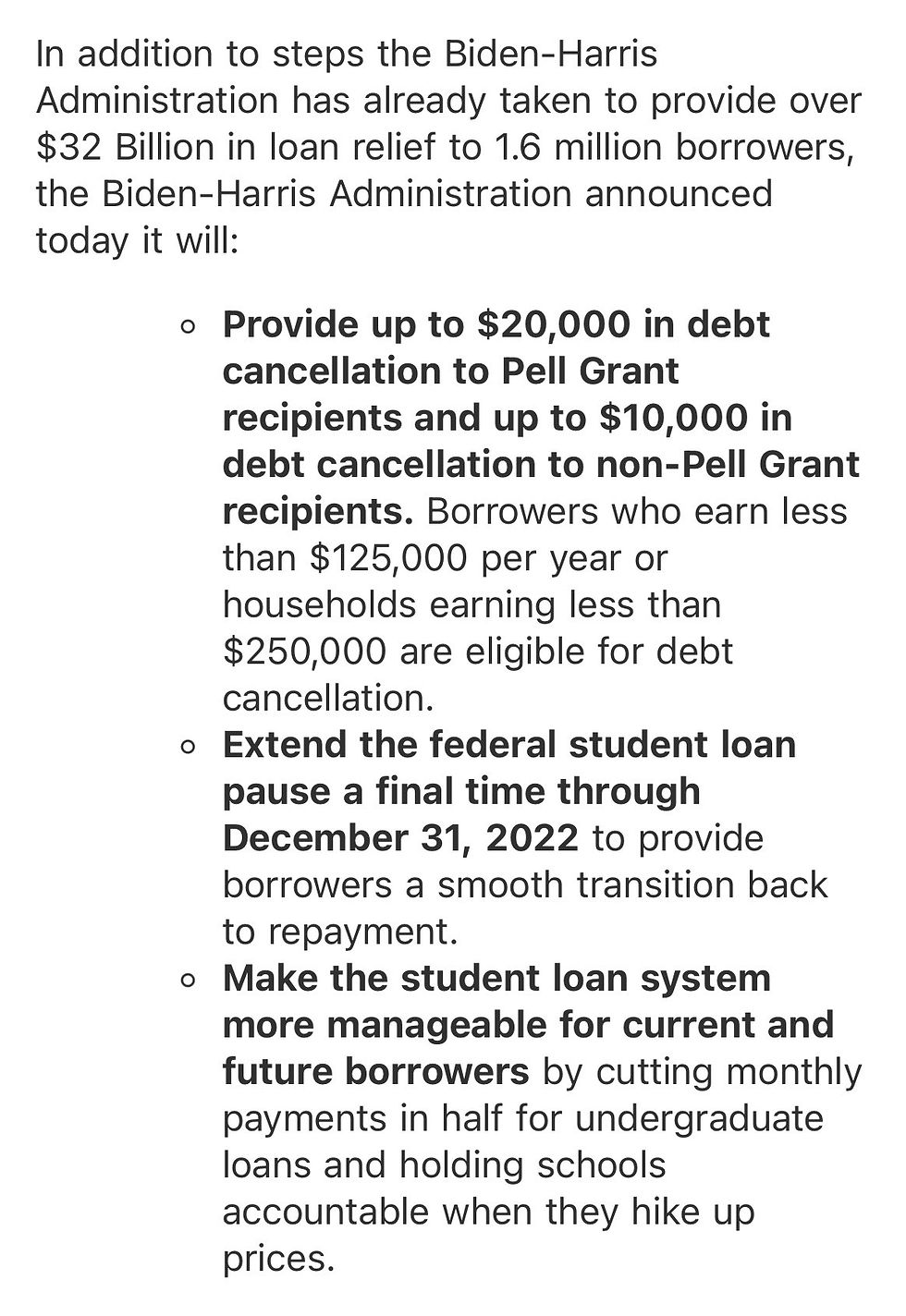

The Biden-era Student Loan Forgiveness Program—struck down in 2023 for similar overreach—serves as a cautionary parallel.

The DOGE initiative is legally precarious in the post-Chevron era. Unless Congress explicitly endorses its mission, courts will likely deem its transformative actions unlawful under the major questions doctrine.

This case underscores a new reality: federal agencies can no longer rely on executive creativity or statutory ambiguity to justify bold reforms. For DOGE to survive, its architects must either secure bipartisan legislative backing or drastically limit its ambitions—a stark reminder that Congress, not the executive branch, holds the pen on major policy shifts.

New chat

Comments