In a landmark judgment in Dr. Tanvi Behl v. Shrey Goel & Ors., the Supreme Court of India reaffirmed a long-standing legal principle: domicile or residence-based reservations in postgraduate (PG) medical courses are unconstitutional. This decision has far-reaching implications for medical admissions across the country, ensuring that merit, rather than geography, remains the primary criterion for selection in higher education.

The Court emphatically stated,

“We are all domiciles in the territory of India. There is nothing like a provincial or state domicile. There is only one domicile. We are all residents of India. Our common bond as citizens and residents of one country gives us the right not only to choose our residence anywhere in India.” This declaration underscores the unity of Indian citizenship and rejects the notion of state-specific domicile for the purpose of reservations.

Background of the Case

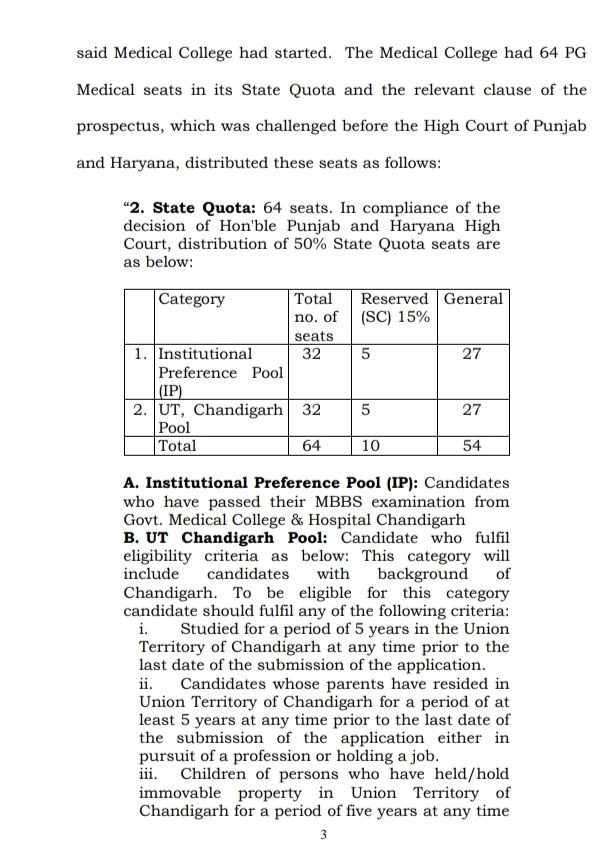

The case originated from petitions filed before the Punjab and Haryana High Court, challenging a provision that granted reservations based on residence in PG medical admissions at Government Medical College and Hospital, Chandigarh. The provision resulted in all 64 seats being filled either by residents of Chandigarh or students who had completed their MBBS from the same institution under institutional preference.

The eligibility criteria for being considered a ‘resident’ of Chandigarh were criticized for being overly broad and lacking rational connection to the objectives sought. For instance, a person who studied in Chandigarh for five years at any point or children of parents who owned property in Chandigarh for five years could claim residency.

The High Court found this provision violative of Article 14 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to equality, and declared the relevant clauses unconstitutional. It directed the medical college to fill the seats based on the merit of candidates as determined by their NEET (National Eligibility cum Entrance Test) rankings.

Residence vs. Merit: The Core Issue

The central question before the Supreme Court was whether a state or union territory could provide reservations in PG medical courses based on residence. The Court answered with a firm “no,” relying on precedents such as Dr. Pradeep Jain v. Union of India (1984) and Saurabh Chaudri v. Union of India (2003), which had previously ruled against such reservations.

The Court emphasized that medical education, particularly at the postgraduate level, is a matter of national interest. Meritocracy must prevail to ensure that the most qualified candidates receive specialized training. Domicile-based reservations, the Court noted, promote regional favoritism and restrict opportunities for deserving students from other states, thereby undermining the principle of equal opportunity.

Institutional Preference: A Limited Exception

While the Court struck down domicile-based reservations, it allowed for institutional preference to a reasonable extent. This exception acknowledges that states invest in their medical colleges and should retain some control over admissions. However, this preference must not override the overarching principle of meritocracy.

Key Precedents Cited

The judgment drew heavily from four landmark cases:

Jagadish Saran v. Union of India (1980): Established that merit should be the primary criterion for admissions to higher education.

Dr. Pradeep Jain v. Union of India (1984): Held that residence-based reservations in medical admissions are unconstitutional.

Saurabh Chaudri v. Union of India (2003): Reiterated the principles laid down in Pradeep Jain and emphasized the importance of merit-based admissions.

State v. Narayandas Mangilal Dayame (1958): Highlighted the constitutional framework of equality and non-discrimination.

The Court also referenced subsequent judgments, such as Magan Mehrotra v. Union of India (2003), Nikhil Himthani v. State of Uttarakhand (2013), and Neil Aurelio Nunes v. Union of India (2022), all of which upheld the principles established in Pradeep Jain.

Key Takeaways from the Judgment

Merit Trumps Residence: PG medical admissions must be based solely on NEET rankings, with limited exceptions for institutional preference.

One India, One Domicile: The Court rejected the concept of state-specific domicile, affirming that Indian citizens have only one domicile: “Domicile of India.”

A Blow to Regional Bias: The ruling curtails “sons of the soil” policies, promoting a unified national talent pool and ensuring equal opportunities for students across the country.

Court’s decision is a significant step toward ensuring fairness and transparency in medical admissions.

The Supreme Court’s ruling upholds the fundamental values of equality and meritocracy in India’s education system. By eliminating residence-based reservations in PG medical courses, the Court has reaffirmed that excellence, not geography, should determine opportunities. This verdict marks a pivotal moment in the evolution of medical education in India, paving the way for a more equitable and merit-based system.

댓글